No Hill Too High

Junior Friends of Jockey’s Ridge

By Betsy DiJulio

Behind many natural wonders are forces of nature. Such is the case with Jockey’s Ridge State Park and Peggy Birkemeier, though she is quick to give credit to legions of others.

Perched between the Atlantic Ocean and Roanoke Sound in Nags Head, Jockey’s Ridge State Park’s 426 acres form the largest natural dune system on the East Coast and the most visited state park in North Carolina. Annual visitation is well over a million, and some years almost two. This awe-inspiring living dune, continually sculpted by Mother Nature, famously swallowed a hotel in the 19th century. Recently, vestiges of an erstwhile miniature golf course have been revealed and concealed in an endless windswept cycle, the crenelated towers of its castle lending a hint of folklore and fantasy.

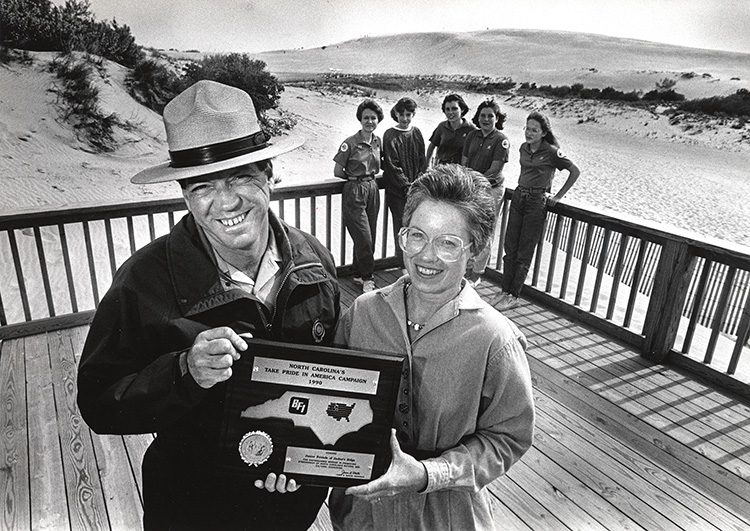

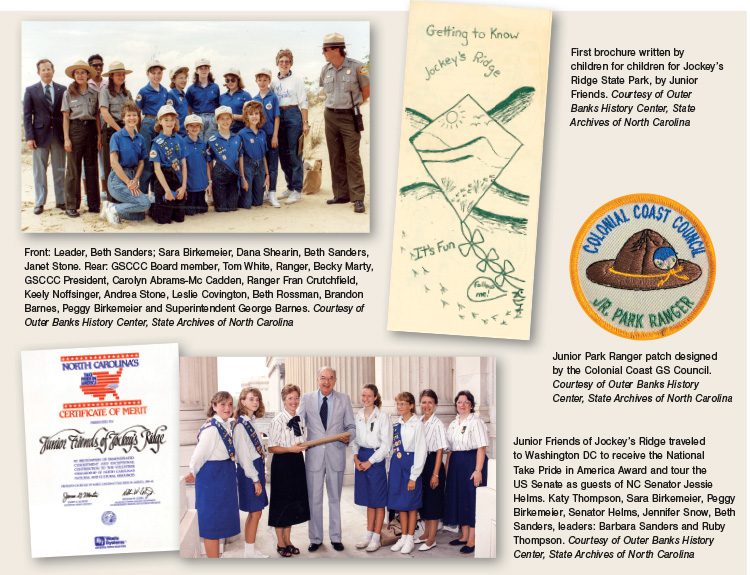

Park Superintendent George Barnes, Peggy Birkemeier. Rear: Barbara Sanders, Sara Birkemeier, Keely Noffsinger, Katy Thompson and Beth Sanders. Photos Courtesy of Outer Banks History Center, State Archives of North Carolina.

Beneath the kite flyers and sandboarders is an ancient geological story that continues. Melting glaciers and rising ocean water, sand carried on the ever-present winds, and periods of vegetation and forest fires all played leading roles in this ongoing drama which, today, involves shrinking dunes, perhaps evidence of this storied stretch of sand’s evolution to a forested state. The desert-like terrain, with its rippling ridges and drifts as high as 90 feet—once 140—exerts a magnetic pull on photographers who find the patterns of light and shadows irresistible, though the surface is becoming dotted with shrubs and grasses.

With three distinct ecosystems—the dunes, the sound, and maritime forest—Jockey’s Ridge, which became a state park in 1975, was ripe for Birkemeier’s brand of environmental, experiential learning. With a professional background in education, a six-year tenure as a Girl Scout executive in New York and Pennsylvania, two daughters, and a husband “with a few different titles” in the field of coastal research, this DC transplant went to work at the confluence of those professional and personal forces.

What began in 1985 as a “huge challenge” emerged in 1987 and continued for five years as the Junior Friends of Jockey’s Ridge for girls ages 10-14, a Girl Scout Special Interest Group with support from the Girl Scouts of the Colonial Coast Council. Though Birkemeier led the charge up the sandy hill, she acknowledges the assistance of “a great team of adults” and expresses gratitude for “the staff at the Council for their support for our programs at Jockey’s Ridge State Park,” including serving as the fiscal agent for program grants.

What started as the Birkmeiers’ desire to “encourage our daughters to enjoy their natural surroundings…and the joys that come with hands on discoveries all around them on the Outer Banks” resulted in a handful of major projects that formed the core of the program: two brochures, trails, a Girl Scout patch, and a specially designed accessible boardwalk that “greatly expanded the use of Jockey’s Ridge.” As for the girls, says Birkemeier, “I can’t say enough about the joy, passion, and curiosity the girls had for all the discoveries they made at Jockey’s Ridge State Park.”

What started as the Birkmeiers’ desire to “encourage our daughters to enjoy their natural surroundings…and the joys that come with hands on discoveries all around them on the Outer Banks” resulted in a handful of major projects that formed the core of the program: two brochures, trails, a Girl Scout patch, and a specially designed accessible boardwalk that “greatly expanded the use of Jockey’s Ridge.” As for the girls, says Birkemeier, “I can’t say enough about the joy, passion, and curiosity the girls had for all the discoveries they made at Jockey’s Ridge State Park.”

The initial brochure—the first in a North Carolina state park to be written by girls for girls—was “Getting to Know Jockey’s Ridge.” Its success was followed in 1988-89 by “Tracks in the Sand,” a brochure funded by a grant from the NC Wildlife Resources Commission that included a new self-guided 1.5-mile nature trail. These research and writing projects immersed the girls from September to May in service projects that afforded them the opportunity to learn about and share the history of the park. Along the way, they acquired and documented in words and images their understanding of natural and manmade changes to the park and its features, identification of plants and animals, animal behaviors, sand analysis at the US Army Corps of Engineers sand analysis lab in Duck, and park-related jobs. As they did a deep dive into animal tracks, they learned about the protection and preservation of animal habits. The resulting brochures were reprinted “thousands and thousands of times,” some 30,000 per year.

The seven criteria for the Junior Park Ranger Patch were not defined until the end of the first brochure project. As Birkemeier explains, Girls Scouts of the USA “did not have a badge for junior age Scouts that fit what we were doing, so we wrote one for Colonial Girls Scouts to approve, which they did. The criteria we wrote were then used as a state park model.”

Leaping forward several decades, Birkemeier reports that her younger daughter, now a Girl Scout leader in Raleigh, recently traveled with her troop to OBX for a weekend of activities. “The whole troop earned the Junior Park Ranger patch with Austin Paul, Park Ranger, and then slept overnight at the Aquarium on Roanoke Island! She was six when I started the Girl Scout group.”

The last project of Birkemeier’s group began in 1989. Dedicated on April 25, 1991, it was their most ambitious: an accessible trail for physically and visually impaired visitors. With hundreds of volunteer hours and some $12,000 raised from state and Outer Banks Foundation grants, the Jaycees, Kitty Hawk Kites, and others—plus the sale of “lots of hot dogs and lemonade” on project workdays—the trail took shape above the shifting sands, complete with narration on cassette and Braille trail markers. In 1990, when all was said and done, the troop garnered two major state and one national award, affording them the opportunity to meet George H. W. Bush and Senator Jesse Helms.

At the conclusion of the accessible trail construction also in 1990, Birkmeier organized the Friends of Jockey’s Ridge, a 501c3 organization that continues today as the support group for the park. According to her, “The Friends were able to develop resources that encouraged more programs at the park for families and in particular, children. The Friends funded the two brochures and the new Junior Park Ranger patch, still being used with some updated modifications today.”

That same year, she was asked to serve as part-time Executive Director of Outer Banks Community Foundation, a position that allowed her to help donors establish charitable giving funds and to distribute grants from unrestricted money to meet local community needs. She went on to serve for 13 years as regional director for the North Carolina Community Foundation. And, though she and her husband Bill now live in Raleigh, she continues to engage in volunteer work through the likes of the North Carolina State Parks Partners Foundation and serve on boards such as the North Carolina Coastal Foundation.

Evidently, you can take the girl out of Jockey’s Ridge State Park, but you can’t take the park out of the girl.